Did you know? More than half of North America’s birds fly to Florida, the Caribbean, or Latin America to spend the winter, including orioles, hummingbirds, ducks, shorebirds, hawks, and more. For centuries, questions about how birds accomplish their amazing journeys, including flight path, length of stay, where they stop along the way, and if they migrate back to the same breeding grounds each spring, remained unanswered. We need these answers now—since 1970, bird populations across North America have plummeted by a whopping three billion individuals. Luckily, modern technology is filling in some of those knowledge gaps.

National Audubon Society installs Motus wildlife tracking stations in locations like Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary as part of its conservation science program. Specialized antennae communicate with tiny transmitters that researchers affix to birds or other wildlife. If the tagged animals’ migratory path crosses within twelve miles of the receiving station, it records data from the tag to a database that is accessible in near-real time. The program unlocks many mysteries of migration and is especially helpful in identifying the locations that migrating birds need for survival, facilitating the prioritization of those locations for conservation.

On August 6, 2023, the Motus wildlife tracking station at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary recorded its first migrating bird of fall: a Red Knot. Red Knots are federally threatened shorebirds that breed in the Canadian Arctic. Each spring, their migratory paths typically take them to locations, called stopovers, along the central Eastern Seaboard. There, they can gorge on horseshoe crab eggs and bivalves before completing the long flight from wintering areas in the Southeast United States/Caribbean and other locations as far south as southern South America before heading towards Arctic breeding grounds.

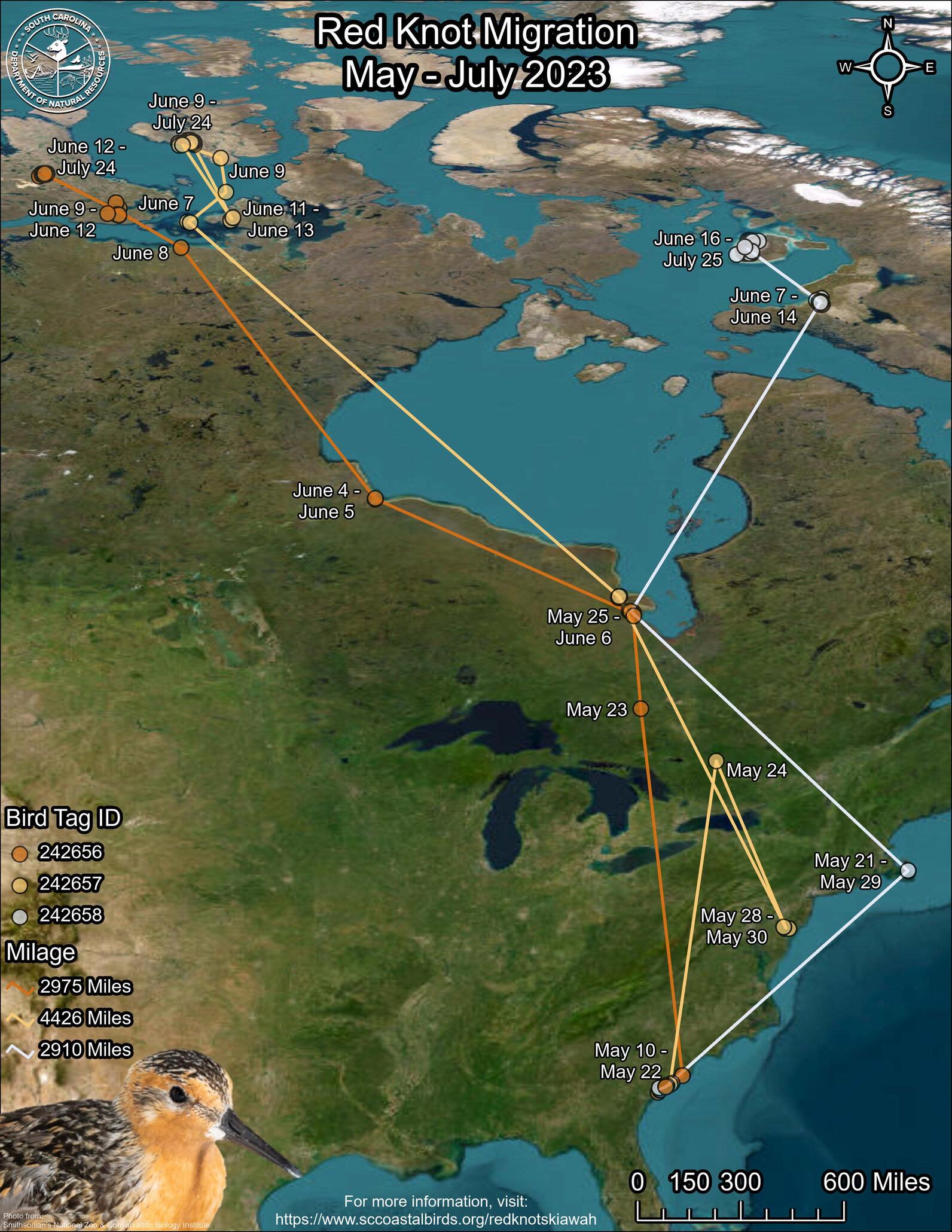

The Motus network website showed that the bird was tagged on May 9, 2023, by South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) wildlife biologists and a team of partners and volunteers. They tagged 40 Red Knots at Kiawah Island, South Carolina to investigate northern migration routes from South Carolina before arriving at their breeding grounds early summer. The conservation of breeding, wintering, and stopover locations remains critical as sea level rise and commercial horseshoe crab harvest increasingly threaten Red Knots and other birds’ survival.

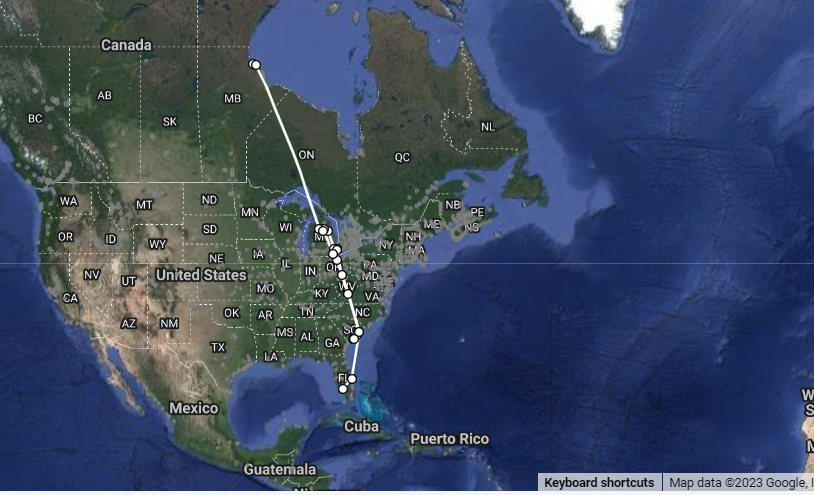

Data from the Motus network confirmed our Red Knot embarked on its northward journey from South Carolina on May 29. By May 30, it had passed by nine Motus stations in West Virginia, Ohio, and Michigan. After it passed a station near Lake Superior, the bird likely continued its northward journey to breed in the high Arctic. It was not detected by a station again until July 13, way up on the shore of Hudson Bay in northern Manitoba, Canada, after its breeding season concluded and southward migration underway.

“Most Red Knots tracked in our study traveled north through the eastern Great Lake Basin, without stopping, thus making the Southeast United States the last terminal stopover for some knots before reaching boreal or Arctic stopover sites,” said Felicia Sanders, the SCDNR project lead.

This Red Knot evaded further detection until August 4, when it pinged a tower in Ohio. Over the following two days, it was picked up by stations in South Carolina and then Vero Beach before crossing Florida near the Corkscrew station. It has not been picked up by another station since that day.

Because the patchwork of Motus stations along its path is incomplete, we may never know where this bird breeds, spends the winter, or if it even reached its winter destination. The perils of migration, worsened by rampant habitat loss, resource competition, and climate change, confirm the need for more data in support of land conservation to curtail the loss of billions more birds in the coming lifetime.

Audubon plays a pivotal role in protecting stopovers as well as breeding and wintering habitat for a variety of migratory birds, including Red Knots. Click here to learn more.

Learn more about the perils of Red Knots' and other birds' migratory paths with the Bird Migration Explorer, a product from Audubon's Migratory Bird Initiative and partners, here.